________________________________

The Forest Practices Board conducted a special investigation into how forestry activities affect wildfire risk reduction (WRR) in BC’s wildland-urban interface (the interface).

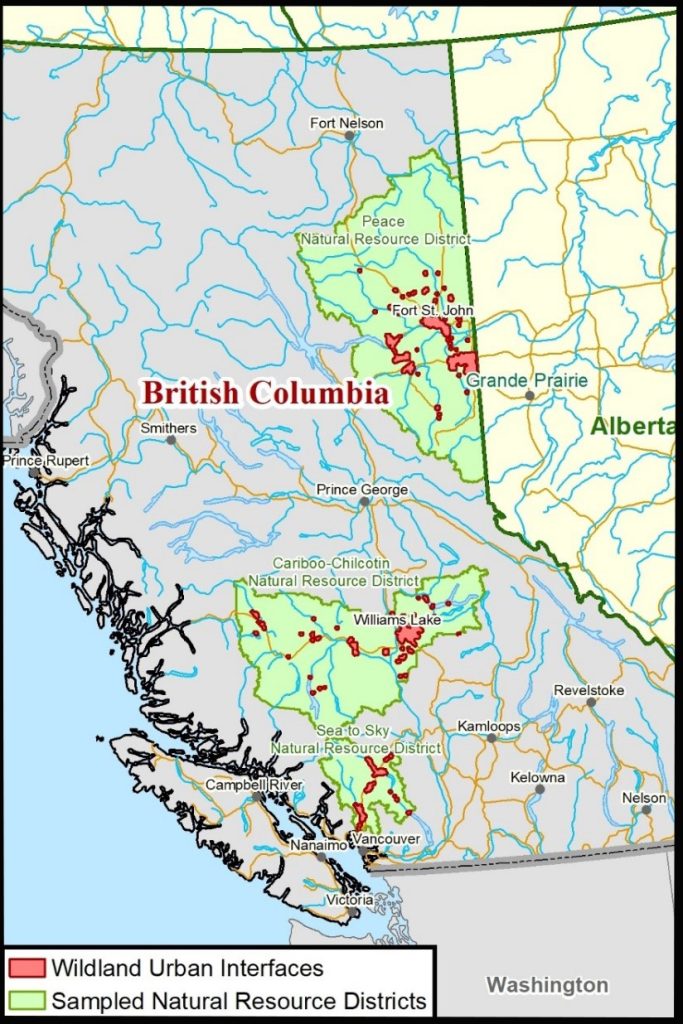

The investigation focused on forestry activities between 2019 and 2022 in the Sea to Sky, Cariboo-Chilcotin, and Peace natural resource districts, specifically in interface areas classified as high or extreme wildfire threats.

The Board evaluated how activities subject to the Forest and Range Practices Act and the Wildfire Act help or hinder WRR efforts within the interface.

This special investigation shows that regulated forestry activities are not reaching their full potential to reduce wildfire risk in the interface. While progress is evident, the imbalance between helpful practices and regulatory barriers continues to hinder forestry’s full potential as a wildfire mitigation tool.

Aligning harvesting with fire risk reduction priorities, requiring faster debris cleanup, expanding the use of fire-resilient regeneration, and improving WRR implementation can help ensure that forestry activities increase wildfire

resilience in the interface.

The Board is calling on the Province to take five actions to strengthen how forestry supports wildfire risk reduction in interface areas. These recommendations aim to:

To read the full list of recommendations, view the full Help or Hinder report.

Fire hazard assessments are often late, incomplete, or based on outdated methods

Fire hazard assessments are a critical requirement for forestry activities. However, only 23% of the fire hazard assessments reviewed by investigators were completed on time, and 30% of assessments did not meet legal content standards.

Professionals who integrated risk assessment into their planning and followed through with abatement reduced fire hazards before they became seasonal liabilities.

Long abatement timelines allow fuel loads to persist through multiple fire seasons

Generally, licensees are reducing wildfire risk by effectively chipping, piling and burning debris, and managing access in high-risk areas. Licensees who aligned planning, accountability and execution showed that timely action is feasible by acting quickly and bundling abatement into harvest plans.

However, the Wildfire Regulation permits logging debris to remain on-site for up to 30 months, keeping flammable materials on the ground across multiple fire seasons. Regulatory compliance can also be met without meaningfully reducing wildfire hazards.

About one-third of sample cutblocks either failed to meet legal abatement requirements or needed further work to comply on time, mostly because professional prescriptions weren’t followed.

The Open Burning Smoke Control Regulation (OBSCR) limits one of the most effective fuel-reduction tools

The OBSCR regulates when burning debris occurs after areas are logged, especially near communities. From 2020 to 2023, few burn windows offered at least two consecutive days, which is required for burning debris.

Despite these challenges, some licensees are adopting alternative strategies. The Cheakamus Community Forest uses custom venting forecasts to identify more burn opportunities. The Líl̓wat Nation purchased an air curtain incinerator, which can allow exemptions to burn in high smoke sensitivity zones.

Municipalities are excluded from the definition of the legal interface, and maps showing the legal interface are not publicly accessible

Fuel hazards closer to the interface must be assessed and abated sooner. However, the definition of ‘legal interface’ excludes municipalities—the most populated areas of the province. This omission undermines risk reduction and can contribute to fuel hazards sitting unabated near communities for multiple fire seasons.

Maps of these legally defined areas, which determine when hazard assessment and abatement must occur, aren’t publicly available. This makes it difficult to verify or enforce compliance.

Wildfire risk reduction treatments are largely effective, but systemic barriers hinder their benefit

Investigators evaluated 22 WRR treatments in the Cariboo-Chilcotin and Sea to Sky districts. No WRR treatment activities were reported in the Peace district between June 2019 and June 2022.

More than 90% of WRR treatments achieved fuel-reduction goals. However, approvals for WRR treatments can take up to a year and there are minimal consequences for non-compliance.

Logging rarely aligns with community wildfire planning

Logging occurs at eleven times the rate of WRR treatments in the interface, yet logging plans rarely coordinate with community WRR planning.

However, some licensees use their harvest operations to support abatement, which shows forestry's capacity to contribute to risk reduction when mitigation is considered.

Silviculture practices remain disconnected from fire resilience goals

Fire management stocking standards have existed since 2016, yet adoption is low. Only 17% of licensees sampled in this special investigation used these standards when regenerating stands.

However, some tenure holders, such as the Líl̓wat Nation, are beginning to design regeneration with fire behaviour in mind, leading the way to more fire-resilient forests.

This investigation took place within the territories of the Blueberry River First Nations, Doig River First Nation, Douglas First Nation, Esk’etemc, Halfway River First Nation, Horse Lake First Nation, Kwantlen First Nation, Lhtako Dene Nation, Líl̓wat Nation, Lillooet Tribal Council, McLeod Lake Indian Band, Musqueam Indian Band, N’Quatqua First Nation, Neskonlith Indian Band, Nooaitch Indian Band, Northern Secwépemc te Qelmúcw, Saulteau First Nations, Samahquam First Nation, Skatin Nations, Squamish Nation, St’át’imc Chiefs Council, Stó:lō Nation, Sts’ailes, Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation, T'it'q'et First Nation, Tsleil-Waututh Nation, Upper Nicola Band, West Moberly First Nations, Whispering Pines/Clinton Indian Band, Williams Lake First Nation, and Xat’sull First Nation.

The Board recognizes the distinct and ongoing relationships these Nations have with their territories and affirms the importance of reflecting Indigenous knowledge, priorities, and rights in forest and wildfire stewardship.